Fuchsia Dunlop is one of the foremost experts in Chinese cuisine, and was one of the first modern Western chefs to be classically trained in China. Two of her books, Revolutionary Chinese Cookbook and Land of Plenty: A Treasury of Authentic Sichuan Cooking serve as my resources for authentic Chinese recipes.

Fuchsia Dunlop is one of the foremost experts in Chinese cuisine, and was one of the first modern Western chefs to be classically trained in China. Two of her books, Revolutionary Chinese Cookbook and Land of Plenty: A Treasury of Authentic Sichuan Cooking serve as my resources for authentic Chinese recipes.

“Fuchsia Dunlop . . . has done more to explain real Chinese cooking to non-Chinese cooks than anyone.” ―Julia Moskin, New York Times

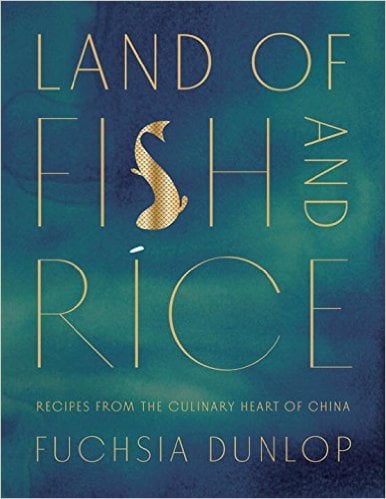

Fuchsia’s latest book, Land of Fish and Rice: Recipes from Culinary Heart of China, focuses on the region south of the Yangtze river, and its modern capitol of Shanghai, called “Jiangnan” region.

The food of Jiangnan is light (unlike Sichuan’s oily, chile-laden food), and as the title of the book suggests, relies heavily on the bounties of the sea and plentiful rice paddies.

The food of Jiangnan is light (unlike Sichuan’s oily, chile-laden food), and as the title of the book suggests, relies heavily on the bounties of the sea and plentiful rice paddies.

This book’s recipes are near and dear to my family – this is the region of my Dad’s hometown cooking. We’re delighted to share with you Fuchsia Dunlop’s recipe for Yangzhou Fried Rice.

Yang zhou chao fan 扬州炒饭 is a fried rice dish that features egg along with leftover bits of ham, shrimp and meat. At Chinese restaurants in America, sometimes the dish is simply referred to as, “House Fried Rice.” Ingredients may differ from day to day, depending on what leftover protein is available.

Yangzhou Fried Rice was invented by Qing China‘s Yi Bingshou (1754–1815) and the dish was named Yangzhou fried rice since Yi was once the regional magistrate of Yangzhou (source)

Excerpt from Land of Fish and Rice: Recipes from Culinary Heart of China by Fuchsia Dunlop. Reprinted with permission.

“Late one night, I dropped into my friend Yang Bin’s restaurant in the old quarter of Yangzhou for a bowlful of noodles, and happened also to meet his cooking master, Huang Wanqi.

Chef Huang started talking about a 2,000-year-old gastronomic text, “The Root of Tastes” (ben wei pian), and told me he thought Yangzhou cooking best represented the subtle magic it described. He went on to explain the mysteries of Yangzhou fried rice, the only dish from this ancient gastronomic capital that has so far achieved international fame. He told me how to cook the secondary ingredients in chicken broth, and discussed the different roles that beaten egg could play in the dish.

“If you begin by frying the beaten egg, and then add the rice,” he said, “you will have ‘golden fragments’ of egg in the rice (sui jin fen). If, instead, you fry the rice and then pour in the egg, the golden liquid coats each grain of rice, so it’s like ‘silver wrapped in gold’ (jin guo yin).” Both, he said, were traditional methods.

You don’t have to go into such detail to appreciate this dish, one of the finest variations on the fried rice theme. The rice is speckled with little nuggets of delicious ingredients and infused with the umami richness of chicken stock.

The following is my version, which omits the hard-to-find luxuries of sea cucumber and freshwater crabmeat, but otherwise follows the traditional method. If you want to make the totally authentic version, add ¾ oz (25g) chopped, soaked dried sea cucumber and ¾ oz (25g) freshwater crabmeat, and substitute tiny freshwater shrimp for the saltwater shrimp.”

Xiao Long Bao is one of the most famous Chinese ste

What you’ll learn: How to make a vegetarian versi

The Chinese culture is filled with food traditions

Ancient Chinese Stir Fry Secrets (at home) Restaura

New friend, Deb Puchalla, who is Editor in Chief of

Copyright © 2000-2018.New Asian Restaurant News All rights reserved.

FEEDBACK